Rotary Engines Explained

Innovative and compact, the rotary engine was once celebrated as a promising breakthrough in automotive technology.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

In the 1960s and ’70s, many automakers believed the rotary engine was the next step in the evolution of the internal-combustion engine. Sometimes called a Wankel engine in honor of its inventor, Felix Wankel, the rotary is lighter and generally simpler than a comparable piston engine. Drawbacks related to efficiency and reliability kept the rotary engine from becoming a viable replacement for the piston engine, however, and most companies—but not all—gave up on the technology during the 1970s.

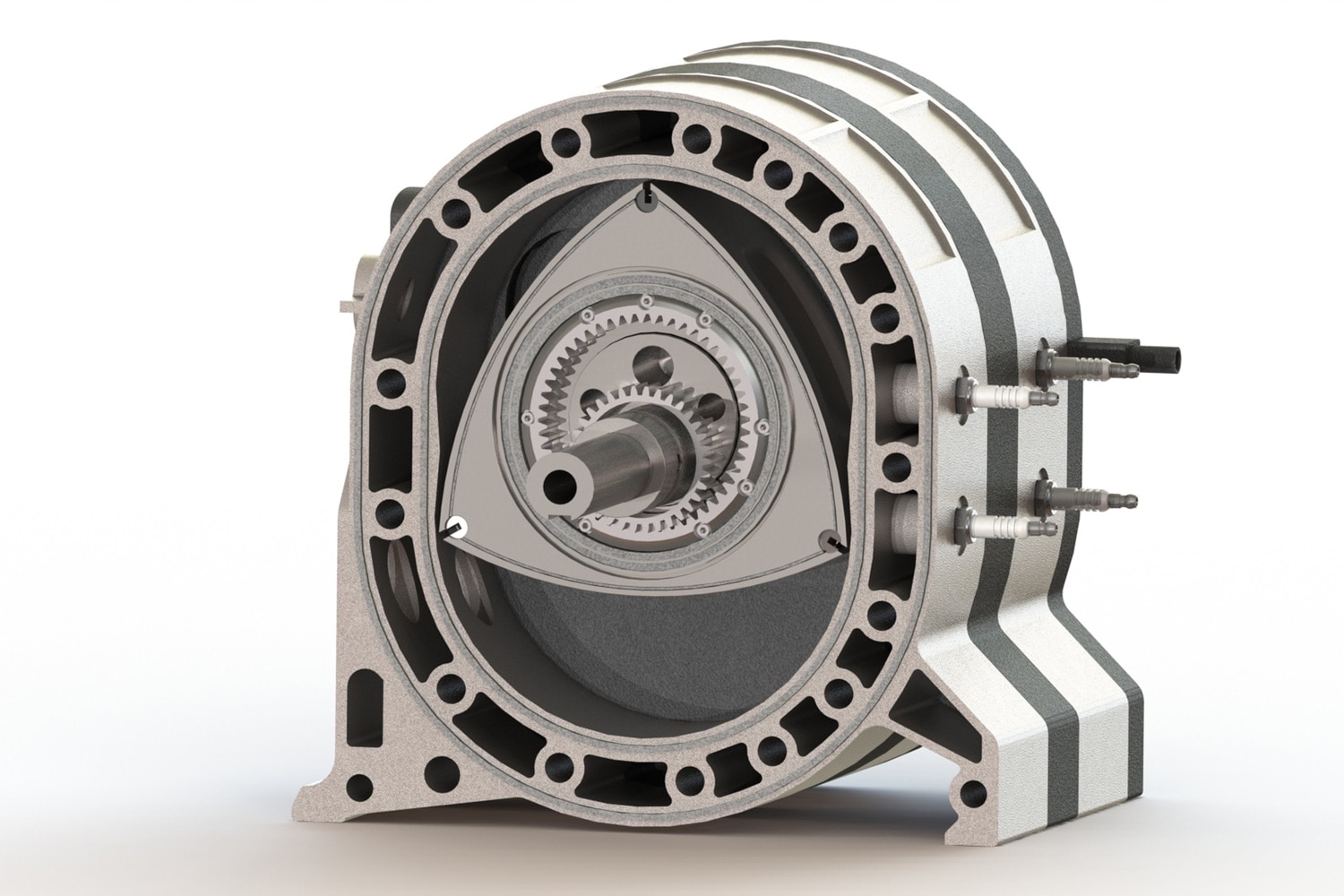

The Rotary Engine’s Basic Layout

Like most piston engines, the rotary engine runs on a mix of fuel and air. In a piston engine, the fuel-air mixture ignites in a cylinder and pushes the piston down to create a rotational force at the crankshaft. In a rotary engine, the fuel-air mixture gets pushed around an oval-ish chamber by a triangle-shaped rotor. There are no valves in a rotary engine, which is a major reason a rotary has roughly 75% fewer moving parts than a piston engine. The lack of a valvetrain and less rotating mass allow a Wankel to rev more freely and to higher speeds, with some able to hit 10,000 rpm.

The air-fuel mixture enters the rotor housing via an intake port. As the rotor spins, it compresses the mixture and moves it toward the part of the housing where the spark plugs are located. The mixture ignites to create the force that keeps the rotor moving, which in turn spins the shaft that sends power to the transmission. The last part of the rotor’s rotation moves the exhaust gases toward and out the exhaust port. Due to this layout, a rotary engine tends to run smoother than a comparable piston engine, and it can develop more power with less displacement.

Many of the rotary engines that historically have been fitted to production cars were two-rotor units. Mercedes-Benz experimented with three- and four-rotor engine designs for the experimental C111, and Mazda won the 1991 24 Hours of Le Mans with the four-rotor 787B.

Famous – and Infamous – Rotary-Powered Cars

General Motors spent a great deal of time and resources trying to perfect the rotary engine, and executives planned to begin building it in limited numbers in the early 1970s. GM licensed the patents for the engine for $50 million and hoped to offer it as an option in the Chevrolet Vega after solving design and production problems.

The Vega was to receive a twin-rotor engine rated at 180 horsepower; General Motors also used this drivetrain to power an experimental Corvette called XP-897 GT that made its debut as a concept car in 1973. Interestingly, the XP-897 GT’s engine was mid-mounted for packaging reasons; it used an engine-transmission combination being developed for use in front-drive vehicles to drive the concept’s rear wheels. Neither the Corvette nor the Vega was ever released with a rotary engine, and GM stopped developing Wankel technology in the mid-’70s.

Ford experimented with the rotary engine, as well. It, too, licensed the design to develop and manufacture its own version of the engine, but it never released a Wankel-powered car. Chrysler wasn’t as optimistic: Alan Loofbourrow, its Engineering Vice President, predicted that the rotary engine “will turn out to be one of the most unbelievable fantasies ever to hit the world auto industry” in a 1972 interview.

Mazda

Mazda

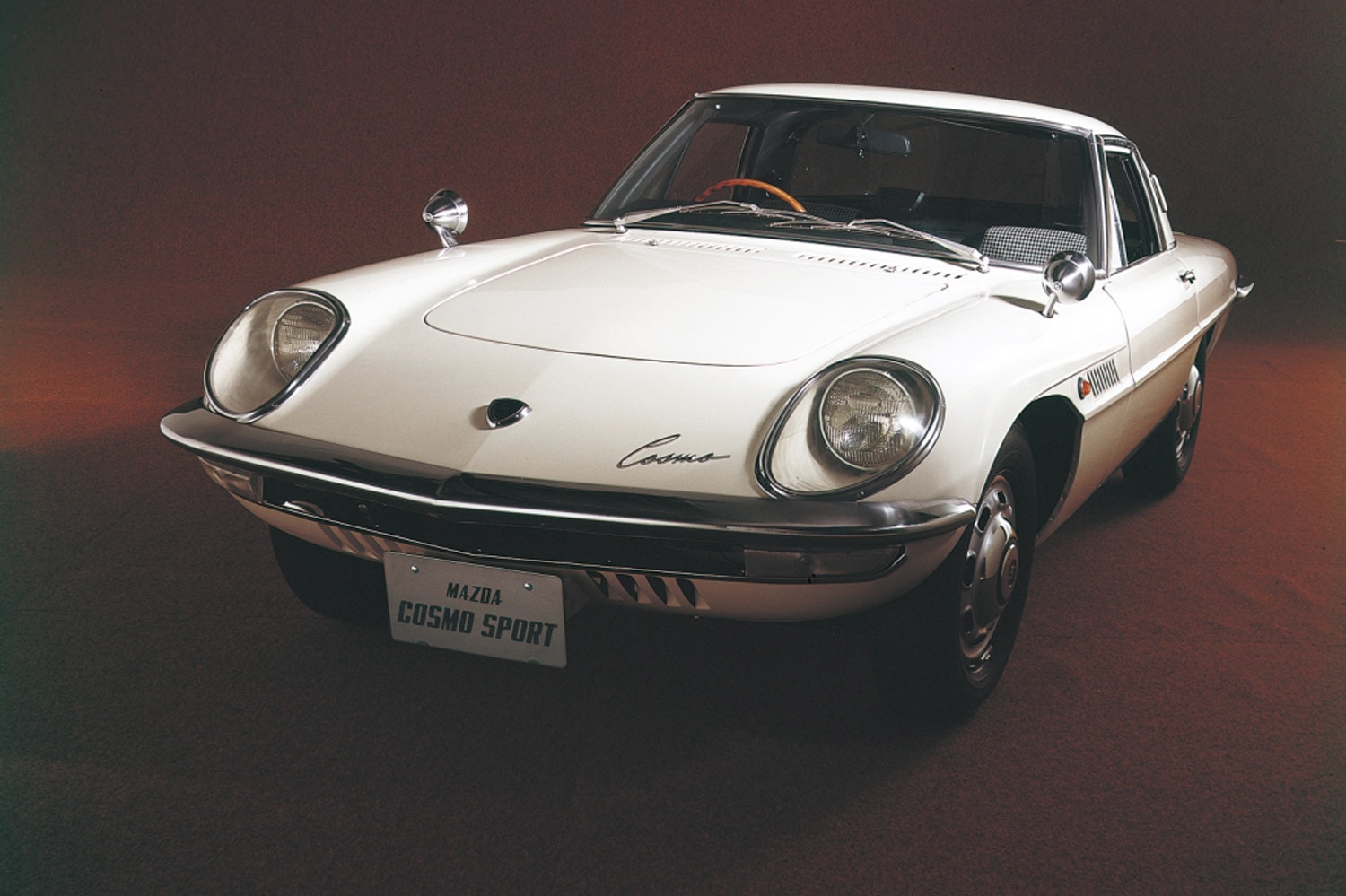

Mazda is the company most often associated with the rotary engine.

The rotary engine became part of Mazda’s identity and powered a long line of RX-badged coupes. The first RX-7 made its debut in 1978, and the nameplate appeared on a total of three generations before it passed the Wankel torch to the RX-8 in 2003. Production of that model ended in 2012, and Mazda hasn’t launched another series-produced rotary-powered car since, though development work continues.

Citroën and NSU were the rotary engine’s strongest proponents in the European market. Based in France and West Germany, respectively, they created a joint-venture called Comotor to design and build rotary engines. Citroën released two models called the M35 and GS Birotor that were built in small numbers. Citroën even built a prototype rotary helicopter in 1973. NSU was more successful: It built its futuristic-looking Ro80 from 1967 to 1977.

Mazda

Mazda

Limited Success – But Not Dead Yet

One of the reasons the rotary engine has seen limited success is because its inherent issues are complicated and expensive to solve. It burns oil and returns relatively low gas mileage, which in turn creates emissions problems. That’s why GM, NSU, and many other manufacturers stopped developing the technology in the wake of the oil embargoes that rocked the 1970s. These issues have become even more amplified in the present day as fuel economy standards get stricter around the world.

Reliability remains one of the rotary engine’s weak points. Apex seals, which seal the rotor’s tips against the chamber wall, tend to wear out, and rotary engines often need a rebuild between 80,000 and 100,000 miles. By comparison, an average piston engine should keep running for 200,000 miles with only normal maintenance.

Mazda

Mazda

This helps explain why there are currently no new regular-production cars equipped with a rotary engine. The saga doesn’t end here, however: Committed to keeping the Wankel engine alive, Mazda confirmed that its MX-30 electric car will be available with a rotary range extender in the coming years. The engine won’t directly spin the wheels; instead, it will generate electricity once the battery’s charge is depleted.

Written by humans.

Edited by humans.

Ronan Glon

Ronan GlonRonan Glon is an American journalist and automotive historian based in France. He enjoys working on old cars and spending time outdoors seeking out his next project car.

Related articles

View more related articles